The poems “Darkness” by Lord Byron

and “An Invite, to Eternity” by John Clare each unravel a potential death – one

of society, and the other, of a poet and his maiden. Each poem also develops a

theme of choice, and how it can become selfish or self-centered. More

specifically, the voice of “An Invite, to Eternity” asks for his maiden to join

him in death, which can be viewed at one time as endearing or as irrational at

another. “Darkness”, on the other hand, portrays a scenario in which men and

women are self-motivated in their efforts to avoid death and its traps. This

contrast between the two poems reveals different perceptions of human resolve

in the acknowledgement of death and peril’s existence.

Although

fantastic descriptions and devastating trials appear again and again, the first

line of “Darkness” notes that it “was not all a dream” (Byron l. 1). In effect,

this provokes the reader to consume the poem as factual or, at least, probable.

Similarly, John Clare writes in “An Invite, to Eternity” that the maiden and

speaker will choose “At once to be and not to be” (Clare l. 21), thus

discarding the Shakespearean query and terming it a conjunction. In both

instances, death is made realistic in its existence, even if its features

remain surreal. Consequently, the poems can become lenses into the human

reaction to a real “death”.

The

speaker of “An Invite, to Eternity” may propose death to his maiden, but he

does not imply the death of his ego. In what is a consensual pursuit of death,

he ruminates on how the skies “around us lie” (l. 24) and as such, posits

himself and the maiden in the center of it all. He suggests that sisters “know

us not” (l. 16), again placing emphasis on them.

Again, the poem itself acts as a person inviting someone else to death and

places the human being as the controller. With this setting in mind, it is very

interesting to dissect intention: is this a selfish manipulation of life, or is

it a well-intentioned plea for a loved one? Rather than ask, “would thou go with me”, the speaker asks

“wilt thou go with me,” (l. 1) as a sign that the poem is not simple a test, as

in the situation of Abraham and God, and instead is a plea in the face of

something imminent.

Throughout

the poem “Darkness”, monstrosity and decline are depicted vividly. Also

depicted are the actions of people, whose hearts “were chill’d into a selfish

prayer for light” (l. 9). This proposal of selfish people roaming the earth is

juxtaposed with the decline of defined social roles and kingdoms and huts

“burned for beacons” (l. 13). The only instance of selflessness comes in the

role of a non-human – a dog. This inclusion may be deliberate, in order to show

how humanity has turned against one another in its fight against darkness and

death. Perhaps as a nod to how realistic the event is, not even the faithful

dog survives. This fact complicates the notion of selflessness being the

ultimate good, as it seems short-sighted for the dog in the end to think of

another. Regardless, the plagues upon the dog and of humanity illustrate the

power of death. For whatever reason, Byron couples this selfishness with the

decline of social institutions and the fact that “the populous and the powerful

was a lump” (l. 70). The selfish pursuits of man, then, are bleak and unruly.

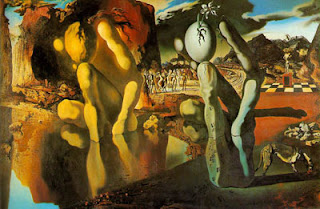

The Metamorphosis of Narcissus (1937) by Salvador Dali

In

each poem, people confront death. Clare points to the “sad non-identity” of

death, and Byron moreover mentions the world as “Seasonless… manless” (l. 71). The

poems are similar in their advocacy for ego, with a lack of communal identity

in “Darkness” and individual identity in “An Invite” seen as unfavorable. In my

reading, though, the speaker of “An Invite” selfishly joins death and requests

for his love to come along, while in “Darkness”, men “selfishly” fight death

and look out for themselves. What is more interesting, in the end, is how one

defines selfishness in the face of death. If acceptance and care for others is

paramount, than the people of “Darkness” are wildly selfish and brutish. Yet,

if those qualities are not, one could see why the faithful dog is foolish. Interestingly, if one puts a premium on care for others, the speaker of “An Invite” can either be read as a selfish promoter of death to

a loved one, or as fool who is faithful to a lover to the point where it kills them both.

So I'm really interested in "An Invite, To Eternity" and it's because of this selfishness question. I'm starting to think "An Invite" is a lot more religious than we might be giving it credit for. One the first read I wondered if the poem is literally to Eternity, making the "sweet maiden" Eternity itself. Then I sort of passed that interpretation off because that would leave the persona hopelessly trying to deflect loneliness by talking to eternity, and on top of that he's asking eternity to spend eternity with him so I feel like that wouldn't work. Then I thought maybe this is literally an invitation to eternity made by a God figure. From the Christian perspective God invites mankind to spend eternity with him, he offers the gift of eternal life, etc. In the second stanza Clare points to Judeo-Christianity by alluding to Abraham (I'm like 80% sure it's Abraham and not someone else in the Old Testament) who by touching a rock makes it spout water for his tribe. "Where stones will turn to flooding streams," Clare says. This is no doubt a promise land allusion. Another way this poem could be more geared toward heaven is its emphasis on the eternal state. There's little mention of some horrific death. The only pseudo unsettling detail is this "sad non-identity."

ReplyDeleteI question how selfish the persona is here partially because the title is an invitation, and their destination doesn't seem all that traumatic. Not sure! Food for thoughts really.