Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem “The

Rime of the Ancyent Marinere,” told in seven parts, reveals itself to be a

lesson to Coleridge’s readers about the implications of mistrusting God and placing

stock in superstitions and myths.

This message is unsurprising when readers realize that Coleridge lived

his life as a Christian. He first

believed in the doctrine of Unitarianism, which postulates that God is just one

person, starkly contrasting the Trinitarian belief of God as three beings

existing consubstantially as one (“Unitarianism”). Later, Coleridge did actually subscribe to the orthodox

Trinitarian beliefs. According to The Longman Anthology of Gothic Verse,

Coleridge had abandoned belief in one God for belief in the Trinity by the time

he wrote “The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere” (Franklin). It is, however, difficult to discern

this fact based on the poem’s text.

There is no doubt, though, that Coleridge was promoting Christian ideals

in this verse.

The

plot of the poem, which employs the unique literary form of a frame narrative,

begins with a scene in which an old mariner accosts a guest outside of a

wedding and entices him to listen to a tale. The mariner’s story is of an ocean voyage on which he lost

his entire crew and suffered supernatural torture because he violated a

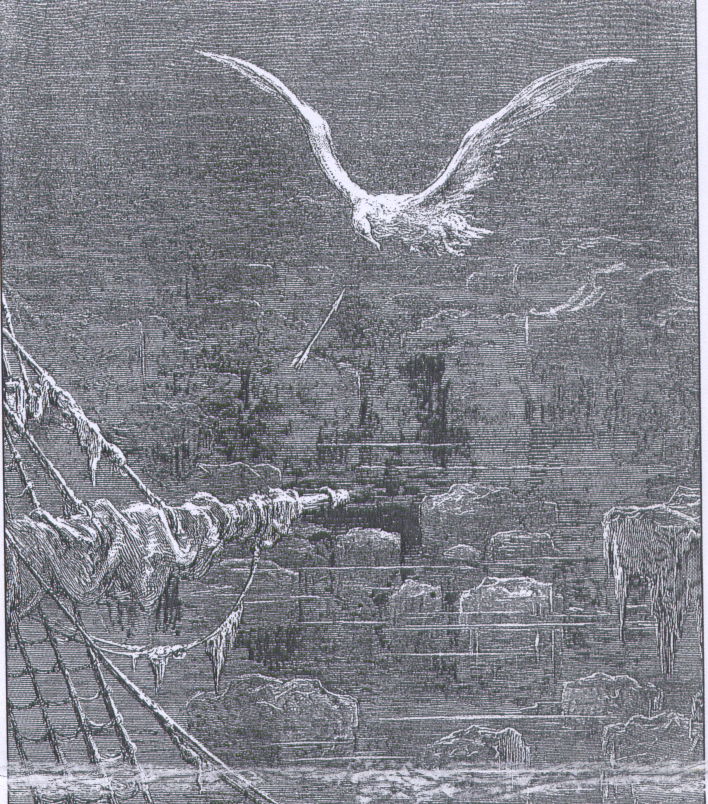

superstition concerning an albatross, a bird of great size. The crew had been struggling through

fog, mist, ice, and stormy weather.

Then an albatross appeared during the tempest and accompanied them on

their journey, at which point a south wind blew and buoyed them onward. It accompanied them, that is, until the

mariner shot the albatross with his crossbow.

The

crew had varying reactions to this incident. Initially, they feared for their lives that the mariner, upon

killing the albatross, had upset the balance and fate would plague them on

their travels. However, the wind

continued to blow and the sun continued to rise so they determined that killing

the albatross actually rid them of the foul weather. Things took a turn for the worse, however. The wind eventually stopped, the ship

was stuck on the ocean, and drought set in. Then the supernatural curses took effect; a ghost ship

visited the crew, all the men dropped dead, and the surviving mariner realized

his curse to endure a living death.

After days of this and once progress had resumed, a band of seraphs

animated the corpses until they abandoned the bodies to serve as a beacon to a

Hermit on the shore who would help the mariner. The mariner is then destined to relay his story to every

deserving soul so that God’s message may be realized.

The

juxtaposition of superstition and Christianity in this poem sets forth an

interesting situation for readers to consider. The poem deals outwardly with sailor superstitions and their

consequences. Shooting an

albatross, a mythically good omen for sea travelers, supposedly brings

misfortune upon the offenders.

That seems to be the case for the mariner, as the wind stops and travel

becomes impossible following the heinous act. Then things spiral further downward as the crew all die and

play bodily hosts to spirits. In

the mariner’s mind, it is no wonder that he sees all these calamities as a

direct result of his shooting the albatross. He is, after all, a sailor and likely buys into the belief

that the status of a bird can determine the fate of a voyage.

It

is intriguing, however, to view the happenings through a different lens, a

Christian lens. This lens posits

the idea that God controls all of the events of the adventure. God would have been the one treating

the sailors to an array of weather: mist, fog, storms, ice, breezes, and

waves. This would have simply been

following his plan. In other

words, all of the weather would have happened regardless of the presence of the

albatross. The mariner’s killing

the albatross is still a grievance, though not one defying superstition. Rather, it is one that defies God’s

commandment not to kill. It is

because the mariner sins against God’s will that he and his crew must suffer

tribulations. As God is an

almighty being, it would not even be outside of his power to kill the crew and

reanimate them with seraphs, or to conjure a fictitious ghost ship to frighten

the mariner and teach him a lesson.

Fate avenging the superstition-plagued albatross or God punishing the

mariner for his disobedience to the faith could both explain all of the

occurrences in the mariner’s tale.

Evidence

to support the position that God was the cause of the mariner’s mishaps, rather

than the supernatural, comes from a careful interpretation of Coleridge’s

text. First, the circumstances

become really bleak once the mariner employs the albatross in an almost

blasphemous manner. After his crew

decides to blame their troubles on his superstition violation, the mariner

enacts his own form of penance.

“Instead of the Cross the Albatross/About my neck was hung” (Coleridge

137-8). Where upon a good

Christian a cross should be seen, the mariner dons the albatross. This likely angers God even further;

not only did the mariner kill one of God’s innocent creatures, he now wears the

dead creature in place of a cross.

It is immediately following this revelation that the ghost ship appears and

the curse begins to set in, very possibly God’s work.

Further evidence comes with the

fact that the mariner only ever calls upon God in his times of need, when he is

especially trouble-laden. He does

not think, when the breeze is blowing and the sun is shining, to acknowledge

God then. A final supportive

example is in the fact that the Hermit saves the mariner. The seraph-band emerges from the corpses

and gives off a light that beckons to the Hermit, who knows they are a signal:

“’Where are those lights so many and fair/That signal made but now?” (Coleridge

558-9). Fate would have no reason

to guide the Hermit to the mariner for rescue. God, however, would want the mariner to be saved and given a

chance to live out his faith properly.

Thus, God arranges the seraphs to steer the Hermit to the mariner for

redemption.

Coleridge’s intention to portray

the mariner’s misfortunes and eventual salvation as acts of God becomes clear

when the mariner reveals his intentions to the wedding guest at the end of the

poem, when the frame story comes back into prevalence. The mariner confides to the wedding

guest that he has “strange power of speech” which when “anguish comes and makes

[him] tell/[His] ghastly aventure,” men cannot help but listen (Coleridge 620;

617-8). It is his duty to impart

his tale on certain people so that they may become wiser and will know and obey

the power of God. He, and in essence Coleridge, wishes to convey

the message that superstitions are superficial interpretations of God’s actions

and that they serve no redemptive purposes, as God does.

Works Cited

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. “The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere in Seven Parts.” Lyrical

Ballads:

With a Few Other Poems (London: Printed for J. & A. Arch, 1798).

Franklin, Caroline, Ed. The Longman Anthology

of Gothic Verse (Great Britain: Pearson

Education Limited, 2011).

“Unitarianism.”

Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia.

13 April 2012. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 23 April 2012. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unitarianism>

Photo Source

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2b/The_rime_of_the_ancient_Mariner_-_Coleridge.jpg

No comments:

Post a Comment